FORT CARLTON PROVINCIAL HISTORIC PARK — Few places in Saskatchewan

are as rich in history as Fort Carlton. The fur-trading post was

constructed on the North Saskatchewan River in 1810, but it owes

its existence to a 17th century English monarch.

|

| - courtesy Saskatchewan

Environment |

| A

lovely setting on the North Saskatchewan River, on the cusp

of parkland and prairie. |

In 1670, King Charles II granted the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC)

an enormous swath of North America called Rupert's Land. Encompassing

all the territory in the Hudson Bay drainage system, Rupert's Land

stretched from present-day northern Quebec all the way to southern

Alberta and part of what's now the Northwest Territories. This vast,

undeveloped region was teeming with fur-bearing animals whose pelts

would bring tremendous returns to the stockholders of HBC, today

the oldest traded company in the English-speaking world.

Charles ruled that the company would have exclusive trading rights

to Rupert's Land, although the French, among others, didn't accept

his edict. For decades, HBC factories on Hudson's and James bays

processed furs delivered to them by First Nations people in the

territory. But competition from French and independent traders eventually

forced the company to take its business inland, closer to the source

of the furs.

The first of almost 100 HBC trading posts created over the next

century was built in 1774 at Cumberland House, located on what's

now the east-central edge of Saskatchewan. Carlton House, which

came to be known as Fort Carlton, was established in 1795 near the

junction of the North and South Saskatchewan rivers. The original

post was abandoned around 1804 and re-established some 150 kms (90

miles) to the southwest, on the South Saskatchewan River. In 1810,

the post was moved west to its present site on the North Saskatchewan

River.

Due to its location, Fort Carlton quickly evolved into a key provisioning

centre in addition to its role as a trading post. Situated at the

banks of the North Saskatchewan River, on the cusp of prairie and

forest adjacent to a major overland trade route linking Fort Garry

to Fort Edmonton, it was perfectly positioned to supply the more

northerly posts with the necessities of life. Fresh meat and pemmican

were obtained through buffalo hunts organized by the fort, and fresh

produce and grains were grown in nearby fields.

For today's visitors to the partially-reconstructed fort, located

an hour north of Saskatoon, the interpretive focus is the fur trade.

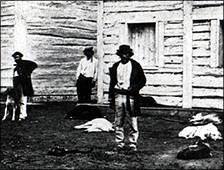

|

| - courtesy Saskatchewan

Environment |

| The

chief factor's house, circa 1880. |

The fur-trading season got underway in autumn, when First Nations

trappers arrived at the post to pick up their 'outfits' - the food,

clothing and other goods required for a winter spent in the forest.

The outfits, purchased 'on credit', were tailored to meet the needs

and wishes of each individual trapper. However, only those with

good credit ratings from previous seasons were allowed to include

convenience and personal items in their outfits.

In spring, the trappers returned to the post to settle their accounts

from the previous autumn. The furs they used to pay for their outfits

were called the 'returns of trade', and HBC clerks used a currency

called the Made Beaver (MB) to determine the value of these returns.

The MB was the value of one beaver pelt, but it was used to calculate

the worth of all furs. And like today's currencies, its value varied

according to shifts in the market. In the 1820s, for instance, a

blanket or a good knife cost two to three MB, while a new rifle

ran about 20-25 MB.

One of three reconstructed buildings within the stockade of Fort

Carlton is the trading shop, where visitors can see examples of

the blankets, beads, pots and pans, knives and rifles First Nations

trappers purchased on their MB accounts. The nearby fur and provisions

store is filled with beaver, fox, mink and other furs that were

appraised here, and then baled by press or lever for shipping to

Hudson's Bay in the spring. The most valuable furs were silver fox,

white ermine, marten and fisher.

The three or four HBC clerks who worked at Fort Carlton at any

given time kept meticulous records of every transaction that occurred

at the post. They were literate men - often Scots, from the Orkney

Islands, who saved their money to purchase land back home. Their

quarters, reproduced at the site, were spartan but comfortable.

According to an interpretive guide, however, their living arrangements

were luxurious compared to the barracks-style facility that housed

laborers, usually Metis (mixed-blood) men and women, who worked

in more menial jobs at the post.

The clerks' superior was the 'chief factor', who was responsible

for the overall operation of the post. For most of the Fort Carlton's

75-year existence, the factor's private residence was located within

the stockade. In 1879, the chief factor of the day had a new residence

built outside the walls of the post, and his reconstructed home

today serves as a modern visitors centre.

Before an American rail line reached Minnesota in 1859, making

overland transportation economically attractive, the large and sturdy

York boat was the primary means of transporting furs and goods between

Hudson's Bay and Fort Carlton. At spring breakup, company employees

at Hudson's Bay set off upstream towards the post, their York boats

brimming with trade goods.

|

| - courtesy Saskatchewan

Environment |

| Metis

laborers were housed in cramped barracks. |

Their arduous journey ended in late summer or early fall, just

in time to stock the post with the goods required for winter outfitting.

But the hard work didn't end there.

The boatmen remained through the winter at Fort Carlton, raising

to perhaps 30 the total number of people who staffed the post in

the cold season. Their time was spent constructing new York boats

or assisting other HBC employees with maintenance tasks. Food was

often short in supply and poor in quality - it wasn't unusual to

find fur in one's pemmican. In spring, as their counterparts left

Hudson's Bay with a new shipment of trade goods, they loaded their

boats with 'returns of trade' and set off downstream for the slightly-less-arduous

journey back to Hudson's Bay.

For better and worse, the fur trade fundamentally changed the way

of life of First Nations people in the North West. It guaranteed

them food and clothing, but made them dependent upon the 'white

man'.

In concert with a nearby First Nations band, Fort Carlton several

years ago began expanding its interpretive program to include the

central role First Nations people played in the fur trade. Just

outside the stockade, several tipis represent the 'tipi village'

that materialized each spring and fall, and stretched as far as

five kms (three miles) down the river bank.

|

| |

| Employees

of the trading shop worked in unheated surroundings due to the

gunpowder on site. |

Inside one of the surprisingly-spacious tipis are examples of the

trade goods First Nations people received in return for their furs.

Rifles were in high demand. But the Cree interpreter on site said

First Nations people seldom used firearms to take fur-bearing animals

- a single bullet hole could greatly diminish the value of a pelt.

They were status symbols, used largely for self-defense or warfare.

First Nations people are solely responsible for the interpretation

provided at the tipi village. To date, their focus has been mostly

cultural in nature. But discussions are underway to expand their

participation in the interpretation of Fort Carlton, especially

regarding important events that occurred in the area.

Treaty Six, the most comprehensive and controversial of the so-called

'numbered treaties', was signed here in 1876 by the Plains and Wood

Cree, and the Crown. It paved the way for European settlement of

Saskatchewan by promising the Cree people land and assistance programs

in return for their claim on the territory.

But it was signed under duress and unfairly executed. More than

100 years after the fact, First Nations people under Treaty Six

are being compensated for these shortcomings through land entitlements

and money.

One of the areas of economic development First Nations people are

pursuing with these new resources is aboriginal tourism. There's

been an expressed interest in creating a facility, in the vicinity

of Fort Carlton, that would interpret treaty and other historical

and cultural developments from a First Nations perspective.

Fort Carlton also played a role in the beginning and end of the

North-West Resistance.

The fur trade gave birth to the Metis, people of First Nations/European

blood. Cree-French Metis from nearby Batoche defeated North-West

Mounted Police based at Fort Carlton in the opening volley of the

North-West Resistance of 1885.

The first of three fires that destroyed the post is said to have

begun accidentally, as police and volunteer militia abandoned Fort

Carlton following their defeat by the Metis. While some historians

question the accidental nature of the first fire - they speculate

it was an attempt to deprive the Metis of a defensible fortress

- there's little argument the next two fires were deliberately set

after the post was evacuated. Plans to rebuild the facility never

materialized.

|

| - courtesy Saskatchewan

Environment |

| The

North-West Mounted Police established a presence at the fort

when Metis in nearby Batoche began agitating for their rights

(circa: 1884). |

Fort Carlton was home to one of the most prominent First Nations

leaders in Saskatchewan history. Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa), the famous

Plains Cree who tried to establish a First Nations coalition to

press the Crown to improve the terms of Treaty Six, was born in

the Fort Carlton area.

During the resistance of 1885, his warriors fought Canadian militia

at Steele Narrows in the last military engagement on Canadian soil.

When Big Bear surrendered to police stationed at Fort Carlton, he

brought to an end one of the most dramatic chapters in Canadian

history.

The park is open daily from the May long weekend to Labour Day.

Snacks, camping, picnic facilities available. For more information, see the provincial government's page on Fort Carlton.

Contact Us

| Contents |

Advertising

| Archives

| Maps

| Events | Search |

Prints 'n Posters | Lodging

Assistance | Golf |

Fishing |

Parks |

Privacy |

© Copyright (1997-2012) Virtual Saskatchewan

|