by Dave Yanko

It's surprising what sticks in the memory months and years after

visiting a place you've not been to before. I won't even guess what

will pop into my head five or 10 years from now when I think about

my first real tour through the Big Muddy Badlands. But I know that

two places left particularly strong impressions with me.

We arrived at the second one after guide Tillie Duncan directed

me to drive up to the lip of the valley to see the only known buffalo

boulder effigy in Canada. As we stood bracing ourselves against

the strong wind buffeting the hilltop, Duncan pointed out the head

and horns of a bison form which, frankly, was difficult to make

out from ground level. It struck me as curious an animal Plains

Indians so revered, so depended upon, was so rarely depicted in

boulder effigy.

Bright purple, red and orange ribbons fastened to a nearby pole

by Indian visitors from the United States are evidence of what's

become an annual pilgrimage to the site, which may well have spiritual

or historical significance beyond the effigy. While walking back

to the car, I caught a darting movement overhead and looked up.

|

| A view

of the valley near the Marshall cemetery. |

A solitary vulture appeared almost motionless as he rode the wind

perhaps 30 metres (100 ft) above. By the time I grabbed my binoculars

from the car, three turkey vultures in side-by-side formation were

gliding above the buffalo effigy and the coloured ribbons. Slim pickings, indeed. But

it was a beautiful and thought-provoking sight.

It was a family cemetery started by pioneer rancher James Marshall,

however, that left the strongest impression.

Marshall, a retired North-West Mounted Police sergeant, at the

turn of the century operated one of the first and largest ranches

on the Canadian side of the Big Muddy. He was an anchor of the area,

one of those pivotal characters whose name turns up again and again

in the history and lore of the valley.

Strange then, it seemed to me as we drove up the hill towards

the cemetery, that this icon of the community would choose a final

resting place so far from anyone else. Then I saw the panoramic

view of the valley below and experienced the serenity of the place

(it's said that some people see a Madonna in the rocks overlooking

the cemetery). If you tour the Big Muddy, check out this spot where

many Marshalls, from far and wide, now rest in peace. It will become

clear why James Marshall loved the Big Muddy.

The Big Muddy Badlands region is located just north of the international

boundary separating south-central Saskatchewan from northeastern

Montana. The badlands are punctuated by the Big Muddy Valley, a

55-km cleft (35 miles) up to 3 kms wide and as much as 160 metres

(500 ft) deep. Carved by melt water during the last ice age, the

valley runs in a southeasterly direction into Montana, where it

meets the Missouri River basin.

It's a large area and there's a lot to see, much of it on private

land. Coronach and District Tours (see bottom of page) provides

guides for $30 plus $10 per person (as of summer 2000). The guide

will provide a vehicle for an additional fee, or you can use your

own, as I did. Tours run from five to seven hours and the distance

travelled can be 150 kms (100 miles).

Hills in the Big Muddy are commonly smooth, rounded and rolling,

covered with natural grass and grazed by cattle. The far more dramatic

scenery includes fascinatingly rugged buttes, cliffs and hogbacks

that reveal the sedimentary layering process that created them over

a series of geological periods beginning 65 million years ago. In

some areas, seams of the coal that's used to fire the nearby Poplar

River power plant can be seen near the surface. The only significant

surface water in the valley is found in Big Muddy Lake and creek,

which all but disappear in a dry summer. In a wet one, they say,

a person can canoe down the creek all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

|

| - courtesy

RCMP Centennial Museum |

| Sitting

Bull |

The Big Muddy is the kind of place Hollywood in the 1950s could

have filmed one of those traditional old dusters, with cowboys trailing

a herd of longhorns through a gulch as 300 Indians peer menacingly

from a butte high above. And the cavalry arrives just in time. .

.

The real stories of the area are more interesting, and unpredictable.

Nearby Wood Mountain is where Lakota (Sioux) medicine man Sitting

Bull took up residence after defeating Custer and the Seventh Cavalry

at the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn. It was from the North-West

Mounted Police post at Wood Mountain that Major James Walsh, one

of Canada's most honorable 'redcoats', made sure 'Bull' obeyed Canadian

law and that Canadian law protected Bull. And it was the distance

from the Wood Mountain post to the Big Muddy that helped make the

latter a haven for outlaws like Butch Cassidy, Sam Kelley and Dutch

Henry.

Wood Mountain post patrols through the Big Muddy were too few

and far between to hamper the outlaws. This, plus the simple fact

this part of the valley was outside of the United States (and therefore

beyond American legal jurisdiction), is why the clever Cassidy used

the area as Station #1 on the famous Outlaw Trail that ran from

here to Mexico. Even after the North-West Mounted Police established

the Big Muddy post in 1902, it was a number of years before the

Mounties gained control of the region.

|

| - courtesy

RCMP Centennial Museum |

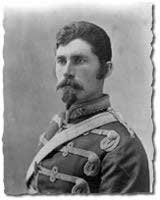

| Maj.

James Walsh |

"Can you imagine trying to patrol this area on horseback?" Duncan

asked, after directing me to the site of Sam Kelley's outlaw caves.

I didn't need to answer.

One of geological features that exemplifies the badlands of the

Big Muddy is Castle Butte, a 70-metre high (200 ft) sandstone and

clay formation located a short drive north of the small community

of Big Beaver. Its prominent position on the flat valley floor made

it a landmark that was used for navigation by Indians, early surveyors,

North-West Mounted Police patrols, outlaws and settlers.

I was disappointed that rain just before our arrival left the

butte too greasy to climb. There are pathways to the top. And I'm told

that with appropriate care and precaution, school kids can make

the hike with ease.

Near the base of the butte, a gray-blue material resembling weathered

wood was strewn around an area covering several square metres. Duncan

told me it was the remains of a petrified tree dislodged by erosion

from the top of the butte. I was skeptical -- it looked like rotten

wood -- until she handed me a piece of the stuff. It weighed

as much as a stone the same size. It'll disappear over the course of the summer,

Duncan predicted.

|

The

landmark Castle Butte

is dotted with caves. |

On the topic of human intrusion, the buffalo effigy and a turtle

effigy near the town of Minton are fenced in but the areas are accessible

by gate. Untold numbers of teepee rings, cairns and other ceremonial

boulder arrangements decorate the hills throughout the Big Muddy.

Many other such boulder allignments have been altered or destroyed.

The area was popular with Indian peoples for several thousand

years or more, according artifacts discovered here. And these Indians

of old spent little time in areas where there was no food. The buffalo

may be gone from the Big Muddy today, but mule deer are certainly

plentiful. A small herd skipped down a steep embankment and slipped

out of sight as we crested a hill on one of the many rugged trails

we traversed in the valley. I spotted them in twos and threes elsewhere.

The badlands is also home to antelope and white-tailed deer, as

well as coyotes, red fox, badgers, weasels, skunks and porcupines.

Wolves that lived on the buffalo and survived in numbers sufficient

to plague early settlers in the region are mostly gone now. One

was shot near Bengough in 1978, after it killed a farmer's pig.

This 'buffalo wolf' is on display at the nature centre in Big Beaver.

Some believe there are still wolves roaming the most remote areas

of the badlands.

Numerous birds of prey thrive in this habitat. Golden eagles, prairie

falcons and the rare burrowing owl are joined by a wide variety

of hawks, including ferruginous, Cooper's, red-tailed, pigeon, sparrow,

marsh and Swainson's. Rattlesnakes have been reported in the area,

but most of Saskatchewan's small, poisonous snake population is

located further west.

|

| Carved

by the elements. |

If you're going to be hiking in the valley, however, you will want

to keep an eye out for the prickly-pear cactus that thrives here

in the higher, sunny areas. Although the climate is dry, it supports

a surprisingly diverse variety of flora.

In fact many people -- including the late RCMP officer Doug Minor,

the last Mountie to patrol the area on horseback in 1938 -- feel

few places can match the beauty of the Big Muddy in spring, when

the cactus and wildflowers are in bloom.

Minor wrote that in addition to the natural beauty and people

of the Big Muddy, some his happiest memories are of the romantic

background of the place. He recalled that as a boy, growing up in Earl

Grey, Saskatchewan, he and his brothers played 'cowboys, outlaws

and Indians'.

"Our heroes were two uncles, and (Big Muddy outlaw) Dutch Henry."

For information on Big Muddy tours, contact Coronach and District

Tours at (306) 267-3312. The Hamlet of Big Beaver is home to a store

as well as the nature centre. You may want to pack a lunch. Joint tours of the power plant and coal mining facility

can be arranged by calling (306) 267-2078. St.

Victor Petroglyphs and Grasslands

National Park are in the vicinity.

Contact Us

| Contents |

Advertising

| Archives

| Maps

| Events | Search |

Prints 'n Posters | Lodging

Assistance | Golf |

Fishing |

Parks |

Privacy |

© Copyright (1997-2012) Virtual Saskatchewan

|