by Dave Yanko

LAC LA RONGE PROVINCIAL PARK -- Although the Churchill River system

is a remote area of beautiful lakes and islands, people have lived

here for hundreds and hundreds of years.

|

| - courtesy Tim Jones |

| A beaver painted

on a rock in the Churchill River system. |

Evidence of this is apparent in the paintings that adorn granite

rocks on the shores of rivers, streams and lakes throughout this

region, as well as in other parts of the Canadian Shield. Some of

the rock paintings depict people, while others illustrate birds,

animals and, possibly, religious icons.

Tim Jones, author of The Aboriginal Rock Paintings of the Churchill

River, says most archaeologists who've studied the paintings

believe they were created by Algonkian-speaking peoples. They're

the ancestors of the Ojibwa, Algonquian and, in the case of the

Churchill region, Wood Cree peoples who still live in the Shield.

But why the paintings were created, or what they mean, is educated

guesswork.

In the 1981 book that grew out of his masters' thesis, Jones addressed

this question by researching aboriginal informants' views of the

paintings, and then considering those comments in light of his own

understanding of aboriginal culture and religious beliefs.

|

| Tim Jones |

"We can reasonably speculate some of them may be paintings of visions,"

Jones said in an interview. "That could be at the individual level.

Or, they could be visions of the more skilled religious practitioners:

the medicine people."

Jones, now executive director of the Saskatchewan Archaeological

Society, says that in traditional Cree belief almost everything

in the material world, both organic and inorganic, had a spirit.

Some of the spirits were kindly, others were malevolent, and all

had to be reckoned with.

"We know the Cree and Ojibwa were expected to have visions -- to

obtain visions to guide them. It was a very individualized approach

to religious experience. Each person was expected to be responsible,

on an every day basis, to the spirit world."

This spirit world, like its material counterpart, could be a dangerous

place. At puberty, each young man was sent out on a 'vision quest'

to find a spirit guide, or spirit helper.

"Very commonly, they would make a nest in a tree, or just climb

up into a tree, and stay there for several days, fasting. Under

those circumstances, they tended to be more susceptible to visits

from different spirits and beings."

In time, a particularly kindly spirit would rise to prominence

during the vision quest. This spirit guide would become the person's

lifelong helper. It would be called upon to provide advice or courage

to help him persevere, says Jones.

|

| - courtesy Tim Jones |

| Jones used transparent

overlays to trace many of the Churchill paintings. |

One of the most commonly represented figures in the Churchill rock

paintings is the thunderbird, an extremely important deity in the

mythology of the Cree and many other North American Indians. Cracking

thunder was believed to be the sound of the thunderbird's wings,

while lightening was said to be flashes from the mighty bird's eyes.

The thunderbird was said to be engaged in an ongoing struggle with

various evil creatures from the underwater or under-earth realms.

The most common of these bad characters -- serpents, as well as panthers

and lynxes with horns -- can also be seen in the rock paintings.

Trying to determine the meaning of the paintings from a modern

perspective and a different cultural context, especially when some

of them may represent the very personal religious experiences of

individuals, is an exercise fraught with potential pitfalls, says

Jones.

"Appreciating the general cultural context is, maybe, as deep as

we can get."

On the other hand, learning more about the age of some of the art

works, at least, appears to be an attainable goal.

Several of the paintings, including one in Saskatchewan, depict

what appear to be rifles. So rock painting appears to have been

carried on into historic times. Figuring out how long ago it began

involves more 'reasoned speculation' that's now being bolstered

by an advanced method of dating organic material.

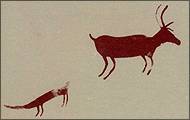

|

| - all reproductions courtesy Tim

Jones |

| Caribou and unidentified

creature. |

Contemporary people living in the Shield appear to go back at least

a thousand years, Jones says, quoting an expert from the Canadian

Museum of Civilization. There's no evident change in movements of

people throughout this period.

About 700 rock-painting sites have been discovered across the Canadian

Shield, from Quebec through Saskatchewan. Michigan and Minnesota,

together, have about 12 sites and Saskatchewan has about 70. Ontario

is home to more than half the known sites, so archaeologists speculate

the tradition began there and spread to Algonkian-speaking peoples

across the Shield.

Quebec has only six sites. But it's there where the experimental

technique was used recently to date a sample of the paint at about

2,000 years old.

Aboriginal rock painters of the Shield used the reddish-brown mineral

ochre as pigment for the their paint. But the longevity of the paintings

is largely due to a tough glue called 'isinglass', an organic substance

made from the swimming bladders of fish and mixed

with the ochre.

Most of the paintings are a foot or less in size. The new dating

technique was used because it requires a much smaller sample of

organic material than what's required by traditional testing. And

while Jones says the new procedure may not yet yield results as

accurate as the established one, he believes the Quebec results

apply equally to older Churchill-system paintings.

"There's no reason to believe the people that made this painting

in Quebec 2,000 years ago -- if that's an accurate date -- are any

different from the people who succeeded them. I think it's quite

possible that it goes back a fair bit further than a thousand years.

We just don't know."

For more information on aboriginal rock paintings, to purchase

Jones' book on the subject (under $10), or for general information

about archaeology in Saskatchewan, contact The Saskatchewan Archaeological

Society at #1 - 1730 Quebec Ave., Saskatoon, SK, S7K 1V9, or phone

(306) 664-4124. Readers may want to see our story about rock carvings found in southern Saskatchewan at St. Victor,

and our feature story about La Ronge Provincial Park, where some rock

paintings are located.

Contact Us

| Contents |

Advertising

| Archives

| Maps

| Events | Search |

Prints 'n Posters | Lodging

Assistance | Golf |

Fishing |

Parks |

Privacy |

© Copyright (1997-2012) Virtual Saskatchewan

|